Andrea E Williamson and Calum Lindsay

Illustrations by Jack Brougham.

People who have ‘no recourse to public funds’ (NRPF) status in the UK are often invisible to public sector statutory services. Due to this citizenship status, they and their families do not have access to the care and safety nets that most of us take for granted. Healthcare access rights also vary across the four UK nations making a complex landscape even more so.

People with NRPF who are in- or pushed out of-the asylum system; vulnerable migrants; are an important group who experience missingness in healthcare.

Missingness is defined as the ‘repeated tendency not to take up offers of care such that it has a negative impact on the person and their life chances’(1).

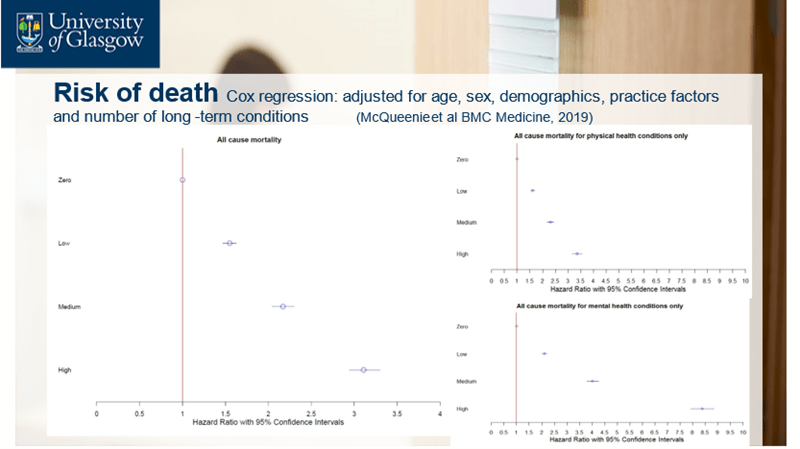

For decades there has been a focus on missed appointments more generally, however this has tended to focus on the impact of missed appointments at the service level such as cost to the NHS of missed appointments(2) rather than at the patient level, and makes no distinction between one off missed appointments and more enduring patterns(3). Our large-scale award winning research investigated patterns of missed appointments at the patient level in the general population for the first time. This was in more than half a million Scottish general practice (GP) patient records.(4).

We found that a high rate of missed GP appointments (an average of more than 2 per year) predicted very high premature death rates. Patients were more likely to have multi-morbidity (2 or more co-existing long term health issues), especially mental health conditions(5), and to experience high socio-economic disadvantage and other challenging social factors(4, 6). Patients experienced high treatment burden – the work needed to manage their health – and missingness in use of acute hospital services too(7).

These graphs(5) shows the chance of dying between the different patterns of missed appointments. If this stark difference in associated outcomes were for a health condition rather than health service utilisation patterns, there would be outrage.

The data is either so poor, or not available for linkage, to be able to know how many people in this epidemiological research were in the asylum system or who experience NRPF. The existing research was sparse also on why people may be missing from healthcare and what could be done to address it. It also tended to problematise the issue as being the fault of patients and an issue for services, rather than the fault of services, and an issue for patients. It was also viewed as being about single issues, hence tended to come up with ‘one size fits all’, reductive solutions(3).

So in our latest research we used realist methods to create a theory about the causes of missingness and to determine what might work, for whom, and under what circumstances, to address these causes. This was a review of 197 published papers(3), interviews with 61people, stakeholder workshops with 16 people to review our results, and further review of the literature to develop our suite of interventions. Our participants were health and care professionals and people with lived experience of missingness from a range of clinical, social and inclusion health contexts. This included vulnerable migrants who have families.

We found that causes of multiple missed appointments occurred across the patient journey and are driven by complex interactions between patients’ circumstances and the ways in which services are designed and delivered.

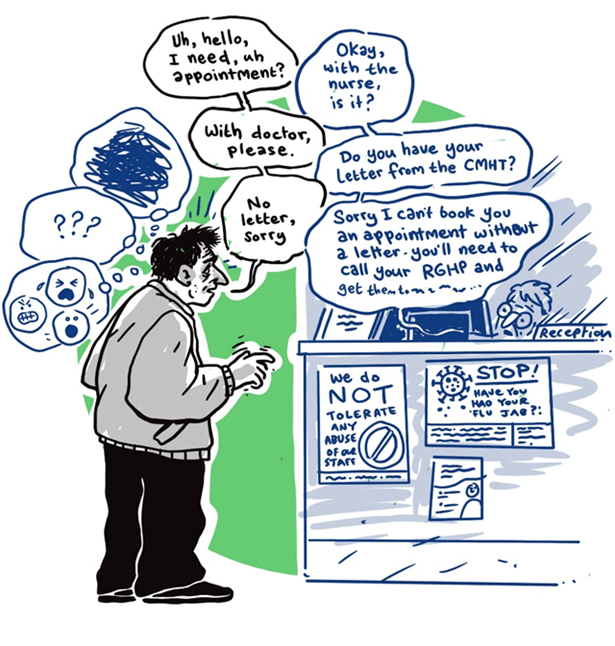

Patients may feel that the service is not for them – not needed, not able to improve their health, not appropriate, or is unsafe. This may be influenced by past experiences of mistreatment, conflicting understandings of health, poor communication, and offers of care in the NHS that do not ‘fit.’

“There’s a constant dynamic of conflict […] and this is a theme you’ll find from anybody you speak to, who has a child or an adult with complex health needs, a constant fight. And some people; they get exhausted, and they give up, and I can’t blame them.” (Jodie, Glasgow)

Some may experience issues physically getting to appointments because of travel costs and difficulties, poor health impeding mobility, and concerns about safety. NHS services have often specific, inflexible rules for how they are used, making it hard for patients to arrange the right appointment for them – at the right time, by the right method, with the right person.

‘Missing’ patients may be subject to a host of competing demands with limited resources to manage or meet them, including work, other appointments, caring responsibilities, or urgent and pressing needs or crises caused by precarious circumstances.

“It’s all very much about the now, where you’re going next. How you’re going to make a living. […] Is it ‘go to the appointment’, or ‘I’ve just been offered this job, which is going to give me a couple of hundred quid in the pocket, which is going to make a difference.” (Naomi, Brighton)

Finally, a lifetime’s worth of experiences of stigma, hostility, trauma, and difficult relationships with care may act as a deterrent against accessing care.

Our suite of interventions developed along with our professionals and experts by experience of missingness is under review for publication. This is aimed at changing the way care is delivered for everyone who is missing from healthcare. A key aspect of this involves changing the attitudes of NHS staff and the wider public – ‘applying and then embedding a missingness lens to health care’. This, along with additional resource for the NHS, will create the conditions to make widespread change.

Tangible positive experiences of healthcare, able to adapt to everyone’s circumstances is required to start closing the health equity gap and realise our ambitions of a healthcare system rooted in human rights. For vulnerable migrants who experience NRPF however, the role of structural barriers in creating and perpetrating missingness(8) is writ so much larger than for any other group. So this NIHR funded research about health outcomes for children and families who experience NRPF with or without section 17 support in England is so vital.

1.Lindsay C, Baruffati D, Mackenzie M, Ellis D, Major M, O’Donnell K, et al. A realist review of the causes of, and current interventions to address ?missingness? in health care. [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review]. NIHR Open Research. 2023;3(33).

2.England N. Missed GP appointments costing NHS millions. UK: NHS England; 2019.

3.Lindsay C, Baruffati D, Mackenzie M, Ellis DA, Major M, O’Donnell CA, et al. Understanding the causes of missingness in primary care: a realist review. BMC Medicine. 2024;22(1):235.

4.Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, McQueenie R, McConnachie A. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7.

5.McQueenie R, Ellis DA, McConnachie A, Wilson P, Williamson AE. Morbidity, mortality and missed appointments in healthcare: a national retrospective data linkage study. BMC Medicine. 2019;17(1):2.

6.Williamson AE, McQueenie R, Ellis DA, McConnachie A, Wilson P. General practice recording of adverse childhood experiences: a retrospective cohort study of GP records. BJGP Open. 2020:bjgpopen20X101011.

7.Williamson AE, McQueenie R, Ellis DA, McConnachie A, Wilson P. ‘Missingness’ in health care: Associations between hospital utilization and missed appointments in general practice. A retrospective cohort study. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253163.

8.Mackenzie M, Baruffati D, Lindsay C, O’Donnell K, Ellis D, Simpson S, et al. Fundamental causation and candidacy: Harnessing explanatory frames to better understand how structural determinants of health inequalities shape disengagement from primary healthcare. Social Science & Medicine. 2025;374:118043.

Leave a comment